'And Then There Were None': Assessing the 2025 Reforms Cutting Jury Trials in England and Wales

Introduction

The UK Government’s 2025 criminal-justice reforms propose one of the most significant structural changes to criminal adjudication in modern times. The reform aims to restrict jury trials for offences attracting sentences under three years, and diverting a large proportion of cases to judge-only or magistrates’ courts. Ministers frame this as an urgent response to the severe Crown Court backlog. Yet the reform strikes at the heart of a centuries-old constitutional safeguard. This article argues that although efficiency is urgently needed, the proposed contraction of jury trial rights risks undermining legitimacy, representativeness, and key Article 6 protections unless accompanied by stronger safeguards.

The Government’s Rationale

The reform is presented as a pragmatic solution to an ‘emergency in our courts,’ [1]. Government figures suggest that rerouting lower-level cases could reduce trial lengths by roughly ‘20%’ [2] and free Crown Court capacity for serious offences. This approach draws on the 2025 update to Sir Brian Leveson’s Independent Review of the Criminal Courts, which concluded that there needs to be ‘structural changes to the courts’ for a ‘fair trial for all involved’ [3]. The Government’s claim is that restricting jury trials is not an ideological shift, but a necessary triage measure to preserve them where they matter most: in serious violence, homicide and sexual offences.

The Constitutional Significance of the Jury

The central controversy arises from the nature of the jury itself. For centuries, English law has treated peer trial as a constitutional safeguard against state overreach. Bushell’s Case (1670) established that jurors cannot be punished for their verdicts, reinforcing their independence. More recently, Lord Devlin famously stated that ‘trial by jury is more than an instrument of justice and more than one wheel of the constitution: it is the lamp that shows that freedom lives.’ [4] Removing juries from a significant proportion of contested cases therefore raises the question: can a system remain constitutionally recognisable if its core democratic feature is substantially narrowed?

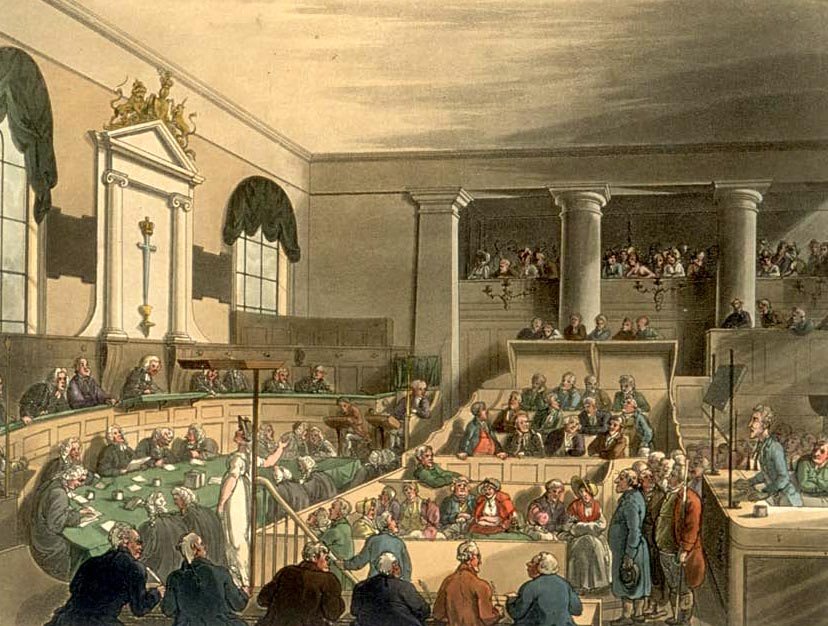

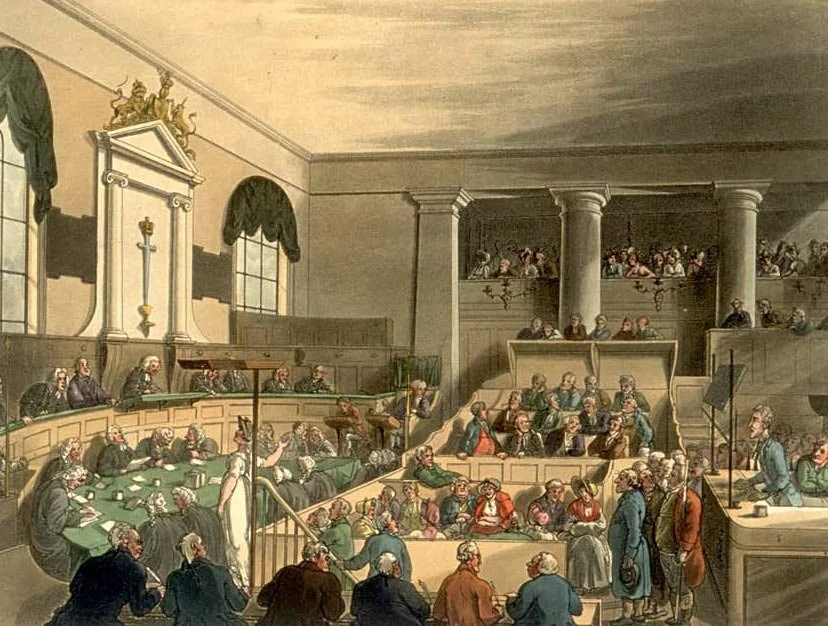

William Henry Pyne and William Combe, Old Bailey in The Microcosm of London or London in Miniature, Volume II, London: Methuen and Company (1904), Wikipedia Commons

Efficiency vs Legitimacy: The Core Tension

The proposed revisions confuse professionals across the criminal bar. The root of backlog, they argue, lies in lack of ‘resources and training’[5]: court closures, judicial shortages, disclosure failures, and ‘progress in introducing technology is uneven’[6]. The Criminal Bar Association has highlighted that jury trials are not the primary source of delay. Critics therefore view the reform as administratively convenient but constitutionally costly.

From a fairness standpoint, diverting cases to magistrates raises representativeness concerns. While impartial and expert, magistrates and judges are not drawn from the general population and thus do not embody diversity like the jury. Therefore removing them risks deepening structural inequalities, particularly for defendants from minority or marginalised backgrounds.

Human Rights and Article 6 Considerations

While Article 6 ECHR does not explicitly guarantee trial by jury, it requires hearings before an ‘independent and impartial tribunal’ [7] and, crucially, fairness in the determination of facts. In cases turning heavily on credibility or community standards, the jury has traditionally been viewed as the appropriate forum. Judge-only trials may be efficient, but they consolidate all fact-finding power in a single state official. This raises legitimate concerns about perceived fairness and public confidence.

Practical Implications

The reforms will reshape the criminal justice landscape. Junior barristers fear reduced advocacy opportunities, which may destabilise the profession. Conversely, victims’ groups welcome potentially faster justice, especially in cases where delays cause trauma and attrition. Ultimately, the success of the reform will depend on whether courts invest sufficiently in judicial training, resources, technological advancements and transparency to maintain confidence in non-jury trials.

Conclusion

In conclusion the 2025 reforms amount to a constitutional experiment: an attempt to reconcile efficiency with tradition by narrowing the scope of jury trials. While the Government’s concerns about delay are real, the proposal risks diluting a cornerstone of criminal justice. Unless supported by robust safeguards, investment, and strict limitations, the reforms may deliver speed at the expense of legitimacy, a trade-off that could reshape public belief in criminal justice for years to come.

[1] UK Parliament ‘Right to Trial by Jury’ (Website, 2025) <https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/2025-11-27/debates/14A1482E-EC3A-49BD-A514-1418F59CB74D/RightToTrialByJury> accessed on 5 December 2025

[2] Daniel Alge ‘Jury trials: what the UK government’s plan to limit them would mean for victims, defendants and courts’ (Website, 2025) <https://theconversation.com/jury-trials-what-the-uk-governments-plan-to-limit-them-would-mean-for-victims-defendants-and-courts-270873> accessed on 4th December 2025

[3] GOV UK. ‘Independent Review of the Criminal Courts’ (Website, 2024) <https://www.gov.uk/guidance/independent-review-of-the-criminal-courts> accessed on 4th December 2025

[4] Susan Ratcliffe Oxford Essential Quotations (4 Ed, OUP, 2016)

[5] UK Parliament ‘Issues affecting courts and the justice system’ (Website, 2024) <https://post.parliament.uk/issues-affecting-courts-and-the-justice-system/> accessed on 5th December 2025

[6] Ibid

[7] Equality and Human Rights Commission ‘Article 6: Right to a fair trial’ (Website, 2021) <https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/human-rights/human-rights-act/article-6-right-fair-trial> accessed on 5th December 2025